No More Stolen Elections!

Unite for Voting Rights and Democratic Elections

Community Democracy, and the Future of Broadband

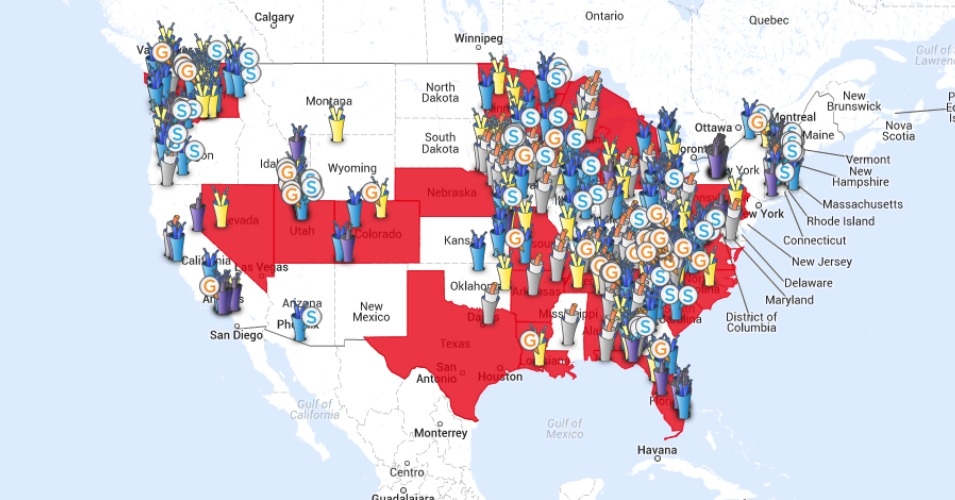

Map shows municipal and locally-controlled broadband networks nationwide. Communities invest in telecommunications networks for a variety of reasons - economic development, improving access to education and health care, price stabilization, etc. They range from massive networks offering a gig to hundreds of thousands in Tennessee to small towns connecting a few local businesses. (Image: Institute for Local Self-Reliance)

In July, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) stirred up a hornets’ nest by announcing it might overturn state prohibitions on municipally owned broadband networks. Republicans protested that Washington should keep its grubby hands off state authority. Giant cable and phone companies contended that local governments are incapable of managing telecommunications networks and the resulting failure will burden taxpayers.

The national debate is both welcome and timely. Welcome because it is grounded while addressing some of the most fundamental issues of our time: What is the role of government? What is the value of competition? What is the meaning of democracy? Timely because we are entering the home stretch of an election year where most state legislators are up for re-election. And because we confront the prospect of two telecommunication mega-mergers—one between Comcast and Time Warner and one between AT&T and DIRECTTV—that may operate under new rules that allow them greater ability to discriminate against other providers.

Some background to the FCC’s decision may be in order. In the early 2000s, exasperated by poor service, high prices and the condescending refusal of cable and phone companies to upgrade their networks, cities began to build their own. Today 150 cities have laid fiber or cable to every address in town. Another 250 offer Internet access to either businesses or residents. About 1,000 have created school or library networks. See map.

The vast majority of these networks have proven wildly successful. The borough of Kutztown, Pennsylvania, for example, saved an estimated $2 million in just the first few years after constructing one of the nation’s first fiber networks, a result of lower rates by the muni network and price reductions by the incumbent cable company in response to competitive pressure. Bristol Virginia estimates its network has saved residents and businesses over $10 million. Lafayette, Louisiana estimates savings of over $90 million. (The benefits of muni networks have been amply catalogued by the Community Broadband Initiative.)

Competition by public networks has spurred cable and phone companies to upgrade. After Monticello, Minnesota moved ahead with its citywide fiber network TDS, its incumbent Telco, began building its own despite having maintained for years that no additional investments were needed. After Lafayette began building its network, incumbent cable company Cox, having previously dismissed customer demands for better service as pure conjecture scrambled to upgrade.

It’s true that some public networks have had significant financial losses, although it is usually bondholders, not taxpayers who feel the pain. But compared to the track record of private telecoms, public sector management may be a paragon of financial probity.

In 2002, after disclosing $2.3 billion in off balance sheet debt and the indictment of five corporate officials for financial shenanigans Adelphia declared bankruptcy. In 2009 Charter collapsed resulting in an $8 billion loss after four executives were indicted for improper financial reporting. In 2009 FairPoint Communications declared bankruptcy, resulting in a loss of more than $1 billion. WorldCom, TNCI, Cordia Communications, AstroTel, Norvergence... the list of private telecommunications companies that have been mismanaged to the point of collapse is long.

We should bear in mind that investors will deduct the losses from their taxes. Thus the cost to taxpayers of private corporate mismanagement arguably has been far greater than that caused by losses in public networks.

In any event, as FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler told a House Communications Subcommittee in May, “I understand that the experience with community broadband is mixed, that there have been both successes and failures. But if municipal governments want to pursue it, they shouldn't be inhibited by state laws that have been adopted at the behest of incumbent providers looking to limit competition.”

If forced to, private companies will compete, but they much prefer to spend tens of millions of dollars buying the votes of state legislators to enact laws that forestall competition rather than spend hundreds of millions to improve their networks.

Today, four states have outright bans on municipal networks. Fifteen others impose severe restrictions. In Utah, for example, if a public network wants to offer retail services, a far more profitable endeavor than providing wholesale services, it must demonstrate that each service provided will have a positive cash flow in its first year!

After five North Carolina cities proved that muni networks could be hugely successful, Time Warner lobbied the state legislature to prohibit any imitators. Dan Ballister, Time Warner’s Director of Communications insisted, “We’re all for competition, as long as people are on a level playing field.”

Level playing field? Time Warner has annual revenues of $18 billion, more than 500 times greater than Salisbury, North Carolina’s $34 million budget. It has 14 million customers while Salisbury’s Fibrant network has about 2500.

Level playing field? Incumbent telephone and cable companies long ago amortized the costs of building their network. When a new competitor enters the market, it must build an entirely new network, passing the costs onto subscribers or investors in the form of higher prices or reduced margins. Large incumbents have far more leverage when negotiating cable channel contracts. A new network serving a single community might pay 25- 50 percent more for its channels.

The law Time Warner wrote and persuaded the North Carolina legislature to pass slants the playing field even more in favor of the giant telecoms. Time Warner can build networks anywhere in North Carolina but the public sector is limited to its municipal boundaries. A public network must price its communication services based on the cost of capital available to private providers even if it can access capital more cheaply.

The North Carolina law, as with many such state laws, prohibits public networks from using surpluses from one part of the city to finance the telecommunications system. But the law doesn’t prohibit private networks from doing so. Time Warner can tap into profits from its vast customer base (largely in uncompetitive areas) to subsidize predatory pricing against muni competition. When Scottsboro, Alabama built a city wide cable network Charter used profits from other markets to offer Scottsboro customers a video package with 150 channels for less than $20 per month, even while Charter was charging customers in nearby communities over $70 for the same package. In a proceeding at the FCC, experts estimated Charter was losing at least $100-$200 year on these deals and even more when factoring in the cost of six major door-to-door marketing campaigns.

Existing North Carolina law already required a referendum before a city can issue bonds to finance a public network. The new law specifically exempts cities from having to obtain voter approval “prior to the sale or discontinuance of the city’s communications network”.

Terry Huval, Director of Lafayette’s LUS Fiber describes still other ways state laws favor incumbents. “While Cox Communications can make rate decisions in a private conference room several states away, Lafayette conducts its business in an open forum, as it should. While Cox can make repeated and periodic requests for documents under the Public Records Law, it is not subject to a corresponding [process of transparency]… Louisiana law limits the ability of a governmental enterprise to advertise, but nothing prevents the incumbent providers from spending millions of dollars in advertising campaigns.”

The FCC’s current proceeding came in response to petitions from two cities: Chattanooga, Tennessee and Wilson, North Carolina. Both have very successful world-class muni networks. Surrounding communities are clamoring to interconnect. The Chattanooga Times Free Press recently described the frustration and anger of people living tantalizingly close to these public networks:

When Joyce Coltrin looks outside the front door of her wholesale plant business, her gaze stops at a spot less than a half mile away.

All she can do is stare in disbelief at the spot in rural Bradley County where access to EPB's fiber-optic service abruptly halts, as mandated under a Tennessee law that has frozen the expansion of the fastest Internet in the Western Hemisphere…the small business owner has no access to wired Internet of any type, despite years of pleas to the private companies that provide broadband in her community.

"The way I see it, Comcast and Charter and AT&T have had 15 years to figure out how to get Internet to us, and they've decided it's not cost-effective," Coltrin said. "We have not been able to get anything because of these state laws, and through no fault of our own, we are treated as second-class citizens. They've just sort of held us hostage."

On July 16, House Republicans voted 221-4 to freeze FCC funding if it attempts to overturn state prohibitions. Sixty Republican House members sent a letter to Wheeler declaring, “Without any doubt, state governments across the country understand and are more attentive to the needs of the American people than unelected federal bureaucrats in Washington, D.C.” Eleven Republican Senators agreed, “States are much closer to their citizens and can meet their needs better than an unelected bureaucracy in Washington, D.C… State political leaders are accountable to the voters who elect them…”

But if state legislatures are closer to and more accountable to the people than the FCC or Congress surely city councils and county commissions are even closer and more accountable.

Ultimately then, this is a fight about democracy. Corporations prefer to fight in 50 remote state capitols rather than 30,000 local communities. But genuine democracy depends on allowing, to the greatest extent possible, those who feel the impact of decisions to be a significant part in the decision making process. Harold DePriest, head of Chattanooga’s municipally owned broadband network (and electricity company) poses the fundamental question this way, “(D)oes our community control our own fate, or does someone else control it?” Decisions about caps and rates and access, about the digital divide and net neutrality can be debated and made at the local level, not in some distant boardroom or having to rely on federal agencies to act and federal courts to support their actions.

If the FCC decides in favor of Chattanooga and Wilson the issue will be tied up in courts for years. But we shouldn’t need the federal government to come to our rescue. The elections this fall will revolve around many issues. But given the centrality of high speed, affordable, reliable broadband and the looming prospect of even more corporate consolidation citizens this issue should be front and center. In 90 days, in 19 states that restrict municipal broadband, voters will be given the chance to overturn that decision by throwing out those who said no to local democracy.

Map shows municipal and locally-controlled broadband networks nationwide. Communities invest in telecommunications networks for a variety of reasons - economic development, improving access to education and health care, price stabilization, etc. They range from massive networks offering a gig to hundreds of thousands in Tennessee to small towns connecting a few local businesses. (Image: Institute for Local Self-Reliance)

GeneralDemocracy SquareLiberty Tree FoundationLiberty Tree FoundationDemocracy SquareLiberty Tree Foundation