No More Stolen Elections!

Unite for Voting Rights and Democratic Elections

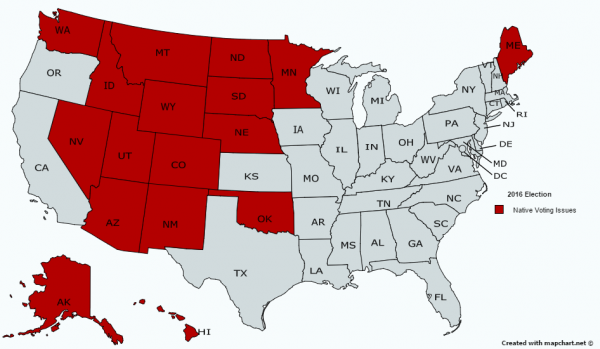

Native Americans across the country sue in attempt to protect voting rights in 2016

The voting rights of American Indians and Alaska Natives have been eroded or ignored since the United States Supreme Court overturned a key provision of the Voting Rights Act in 2013, according to charges in numerous lawsuits brought by tribes throughout Indian country in the battle to protect Native suffrage. A review by ICTMN has found that major litigation is pending all over the electoral map in key voting districts, in which tribes allege that state and local municipalities have imposed a litany of restrictive legislation and tactics aimed at denying Indian voters full access to the electoral process.

— In Utah, the Navajo Nation has brought suit against San Juan County, the state’s largest, for gerrymandering the county’s districts to lessen the impact of the Native majority; a second suit by the nation claims voting access was unfairly restricted, with some Navajo driving upwards of ten hours round-trip to polling stations.

— In Montana, the Blackfeet Nation is pursuing parity between Natives and non-Natives for late registration access and absentee ballots.

— In North Dakota, tribal citizens are suing to overturn new, restrictive voter identification laws.

— In Alaska, an historic suit to improve voter access and language assistance in remote areas was settled; the called-for changes must now be implemented.

— In South Dakota, in Poor Bear v. Jackson County four enrolled members of the Oglala Sioux Tribe alleges that Jackson County’s refusal to open a satellite office for in-person absentee voting and registration on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

— In Arizona, tribal members who use post office boxes on their IDs because they have no official address have been purged from the rolls or placed on a “suspense” list because they live in remote rural areas with no street names.

Importantly, some of these cases may not be resolved in time for the general elections in November. This voting season will be the first presidential election since the United States Supreme Court overturned a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, enacted in 1965 to prohibit discrimination against racial or linguistic minorities, in Shelby County v. Holder (2013).

At the time, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the majority in a narrow 5-4 decision that released jurisdictions from a provision that mandated federal preclearance for any changing to voting practices. Tribal lawyers, scholars and voting rights experts predicted then and charge now that jurisdictions which have historically deprived and suppressed American Indian electoral participation have since operated virtually unchecked.

Almost immediately after the 2013 decision, states and counties moved swiftly to enact more restrictive voter identification laws; close and/or move polling places further away from Indian reservations and Indian communities; purge voter rolls; limit access to late registration and absentee ballots; initiate “mail-only” balloting; and ignore provisions in the act which require access to translation and other forms of assistance for voters who may have limited language or literacy, according to voting rights experts.

Moreover, tribal nations have been forced to sue election commissions for their refusal to redraw voting districts based on current Census data―known as “packing”―in order to maintain a white majority in voting districts which are, in fact, majority Native.

The return to “case-by-case” litigation has shifted the burden from the states to the tribal governments and individual tribal members to challenge discriminatory voting practices and county election commissions who continue to engage in gerrymandering and denial of ballot access, say tribal leaders. Resolving these issues after the fact has been enormously expensive and time consuming for tribes where many of their members live below the poverty line in remote areas with limited resources.

“It’s a very bad trend,” said Laughlin McDonald, special counsel and director emeritus of the Voting Rights Project for the American Civil Liberties Union. “There is an illusion that we have a society based on democracy, but it was founded on the aristocracy of the white male property owner. This is merely the continuance of a long history of limiting the right to vote, so this isn’t new. Voter suppression has been the reality since the beginning.”

Thus, tribal leaders say that the combined efforts by the states amount to a discernible pattern of Native voter disenfranchisement.

“The reality is that preclearance was necessary in some jurisdictions that have historically been bad actors,” said Troy Eid, co-chairman of the American Indian Law Practice at Greenberg Traurig law firm. “The fact that preclearance is no longer required of state and local municipalities in regards to their voting procedures was going to lead to this kind of litigation to ensure the voting rights of Indian people.”

Eid, who is the former chairman of the Indian Law and Order Commission, points to two recent lawsuits by the Navajo Nation in San Juan County, which is the largest county in Utah. In 2012, the tribe sued the county in federal court over the “mal-apportionment” of election districts which favored the white minority. Notably, Utah was one of the last states in the country to legally allow Indian voting in 1957 after a bitter legal fight that went to the Supreme Court.

In this case, the Navajo residents are the majority population in San Juan County, according to the latest Census data. But the county election commission refused to reapportion the districts based on current numbers―district lines that had remained in place for nearly three decades. By “packing” Native voters into one district, the San Juan County Election Commission all but ensured white control over the county election commission, the election process and the school board.

“In enacting the reapportionment, the County did not utilize current, available data and technology to reapportion Commission election districts, despite the offers of up-to-date information and technical assistance extended by the Nation’s representatives,” according to the tribe’s petition.

On February 21, federal District Judge Robert Shelby ordered the county lines redrawn, writing in his opinion that the county’s refusal to reapportion “offends democratic principles.”

Only four days later, however, the Navajo Nation was again forced to sue San Juan County in the U.S. District Court of Utah over its decision to close all polling places and switching to a “mail only” voting system, which the tribe says adversely impacts its members, alleging that some tribal members did not receive their mailed ballots in the 2014 election cycle. The only polling place allowed to remain in operation was placed in the mostly-white town of Monticello in the northern part the county, which is not on the reservation.

In the last election, some tribal members were forced to drive between nine and 10 hours round trip to cast their vote, according to the Navajo Nation. The closure of polling stations, the tribe contends, is particularly burdensome for tribal members with no access to reliable public or private transportation, poor road conditions and lack of resources to pay for gas, since many live below the poverty line. Additionally, many Navajo residents prefer to vote in person, to ensure that their ballot is properly handled and accounted for, to troubleshoot any problems, or to receive translation services or other assistance that are required under the VRA but not available with mail-in ballots.

“The closure of polling places within or accessible to the Navajo Nation Reservation together with the adoption of mail-only voting unreasonably hindered the ability of Navajo citizens in San Juan 2014 general election,” the tribe said in its petition. “And unless enjoined by this Court, these practices will continue to do so in the 2016 election cycle and beyond.”

But the Navajo Nation isn’t the only tribe that has turned to the courts to ensure that ballot access is available to tribal members.

On February 23, the Blackfeet Nation of Montana rejected an offer from the Pondera County commissioners offering 10 hours of access to late registration and absentee ballots, pointing out that non-Indian voters off the reservation are allowed 188 hours by contrast.

In his letter to the county commissioners, tribal chairman Harry Barnes not only objected to the tribe being asked to pay for its own satellite office, but added, “We do not accept the current inequality of zero access nor do we accept your offer that would still advantage non-Indian, off-reservation Pondera County citizens by a 19-to-1 ratio over our Blackfeet Tribal members in ballot access.”

The issue arose from Wandering Medicine v. McCulloch, a 2012 lawsuit in which the Northern Cheyenne, the Crow Tribe, and the Gros Ventre and Assiniboine Tribes sued Montana Secretary of State Linda McCulloch and election commissions in Rosebud, Blaine and Big Horn Counties for their failure to establish satellite offices on three of the state’s reservations to handle in-person late registration and in-person absentee voting.

In March 2014, U.S. District Court Judge Donald Molloy ordered McCulloch to direct Montana counties to establish satellite-voting offices on those Indian reservations within their boundaries. McCulloch announced on February 1 that five new election offices would open on tribal lands this year, and Pondera County commissioners told theGreat Falls Tribunethat they hope to resolve the access issues for the Blackfeet and are working with the tribe.

In January, the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) and several other attorneys filed suit on behalf of seven members of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in North Dakota after they were denied access to ballots in the 2014 election. The tribal members brought their IDs with them to the polls expecting to vote, but were turned away because their addresses were not listed on them.

In Brakebill v. Jaeger, the plaintiffs are challenging North Dakota’s newly-enacted voter identification law alleging that it disproportionately burdens Native Americans and deprives qualified voters of their right to vote. North Dakota is notable for the fact that it is the only state in the nation without formal voter registration, which it abolished in 1951, according to the state’s website.

Under the new legislation, North Dakota now requires voters to present one of only four qualifying IDs which must include a current residential address in order to vote and no longer provides a “fail-safe” mechanism such as provisional balloting that would allow voters to produce their IDs within a few days of the election or an affidavit of identity. North Dakota does not allow the use of military IDs or U.S. passports as a valid form of identification. Although the state does allow tribal IDs, some tribes do not list addresses.

The suit alleges that the new requirements “arbitrarily and unnecessarily” burdens many Native voters in the state for one major reason: There are no Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) locations on any of the five Indian reservations in North Dakota. For many tribal members, who live below the poverty line in remote regions of the state, the ability to travel to and from a DMV can be difficult for a variety of reasons. The tribal plaintiffs argue that their current IDs should not prohibit them from their right to vote.

In spite of the new litigation, however, NARF staff attorney Matthew Campbell said that there was no guarantee that the issue would be resolved by the general election in November.

In October 2015, NARF also settled an historic suit against the State of Alaska in which the tribal plaintiffs were seeking language assistance, more accurate translations of voting materials and improved ballot access for the state’s remote Yup’ik and Gwich’in communities―many of which are so remote that they can only be accessed by bush plane.

"The question of whether Alaska Natives have fair access to the voting booth has been litigated multiple times over the past several years," Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) told the Associated Press. "Impediments to voting in many of our rural communities because of distance and language need to be addressed, and my hope is that this legislation will resolve these issues. Every Alaskan deserves a meaningful chance to vote."

In the absence of a national, legislative remedy (see Legislation For Native Voting Rights Stalled In Congress) tribal lawyers and election watchers say that by challenging state and local laws through Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, tribal nations are using the only means they have left to regain crucial rights that have been lost or ignored since theHolderdecision opened the door for states to abrogate Native voting rights.

“Native Americans have been the most suppressed in our society when it comes to voting rights,” said Brian Cladoosby, chairman of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community in Washington State and president of the National Congress of American Indians. “We were the last to be recognized as citizens of our own country and even then our elders were turned away from voting booths.

“To this day, many tribal governments still don’t have polling places in their communities and tribal members still have to travel hundreds of miles to cast their votes―which is a denial of the most basic civil right we have as Americans. We should not have to individually sue every jurisdiction to force them to follow the law. That was not the intent of the Voting Rights Act.”

Read more athttp://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2016/03/08/will-natives-get-fair-chance-vote-2016-not-according-many-lawsuits-163673?page=0%2C1&nopaging=1Democracy SquareLiberty Tree FoundationNo More Stolen ElectionsNo More Stolen ElectionsDemocracy SquareLiberty Tree FoundationNo More Stolen Elections